The 1970s are generally regarded as one of the best decades in film history. After the golden age of Hollywood came to an end and the Hays code was abolished in 1968, it was time for a new breed of filmmaker to come in – fresh independent talent flourished and cinema suddenly had freedoms that had not been experienced before.

One genre that benefitted from this loosening of the rules would definitely be the crime genre. The dark allegories and hints of the film noir era were no longer necessary as filmmakers now had full freedom to display violence and sordid actions with a bloody bludgeon rather than the careful metaphors that had to be used before. This is not to say that the 70s lacked subtlety, but rather that they had a whole new range of cinematic tools to reckon with and as such there were a wide range of sleazy thrillers, outrageous comedies and gritty gangster flicks that came to life this decade.

There are several iconic crime films from the ’70s, including Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, Roman Polanski’s Chinatown and William Friedkin’s The French Connection, which are all rightly regarded as some of the utmost pinnacles of the genre. However, for this list, we wanted to stay away from films that most people will have heard of and hopefully seen, and instead shine a spotlight on some crime films released in the 1970s that have not been paid the same attention and definitely deserve revisiting.

First, a few honourable mentions:

The Laughing Policeman (Stuart Rosenberg, 1973)

The Seven-Ups (Philip D’Antoni, 1973)

The Gambler (Karel Reisz, 1974)

Rolling Thunder (John Flynn, 1977)

Straight Time (Ulu Grosbard, 1978)

And now, in no particular order…

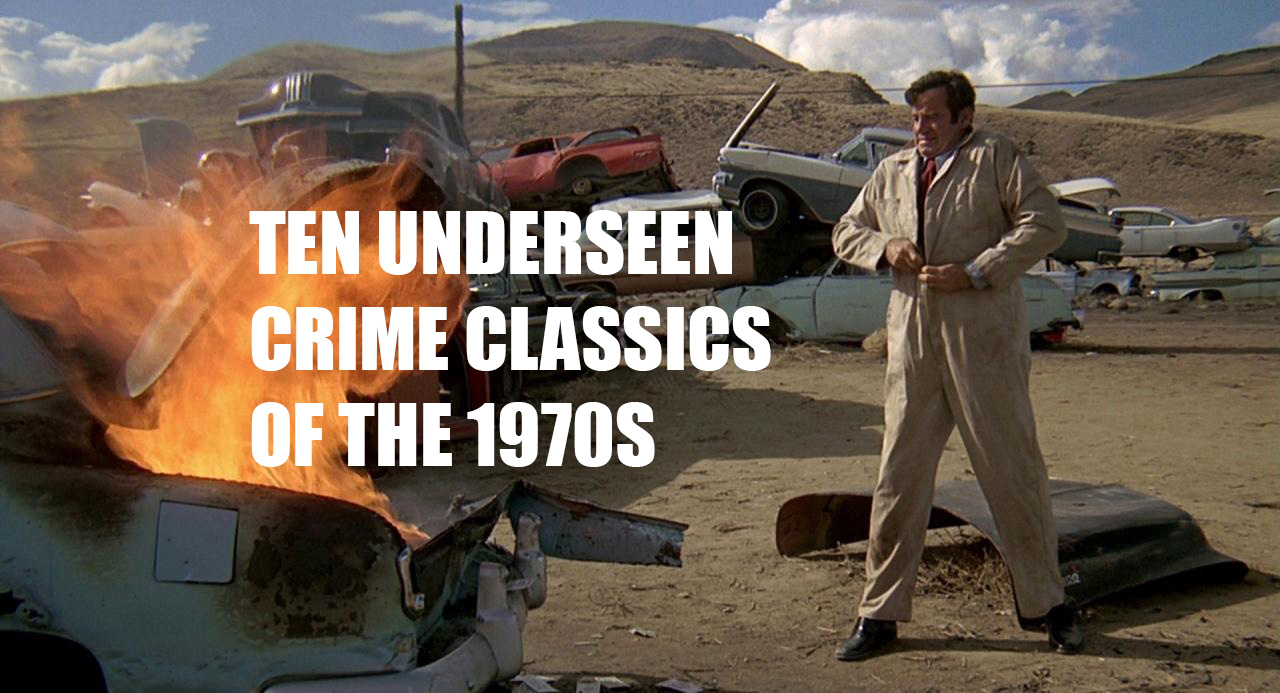

TEN UNDERRATED CRIME FILMS OF THE 1970s:

The Super Cops (Gordon Parks, 1974)

Crime films based on true stories often embellish the facts in favour of providing their audiences with entertainment, but in the 1970s there was a certain movement towards displaying gritty realities and films weren’t afraid of going to cynical or bleak places.

Directed by Gordon Parks of Shaft fame, The Super Cops stars Ron Leibman (who you might recognise as Rachel’s dad from Friends) and David Selby as Greenberg & Hantz, two New York detectives who became known on the streets as Batman & Robin for their vigilante methods – the pair refused to bow down to the rampant corruption of the era and were as much interested in taking down criminals as they were exposing crooked cops.

Like many films of the era, there is lots of on location shooting in the streets and the action is hectic and fast paced with a deft comedic touch. This is a sort of prototype buddy cop film, which would become a staple of the ’80s, and one that Edgar Wright noted as a strong influence on Hot Fuzz.

Going in Style (Martin Brest, 1979)

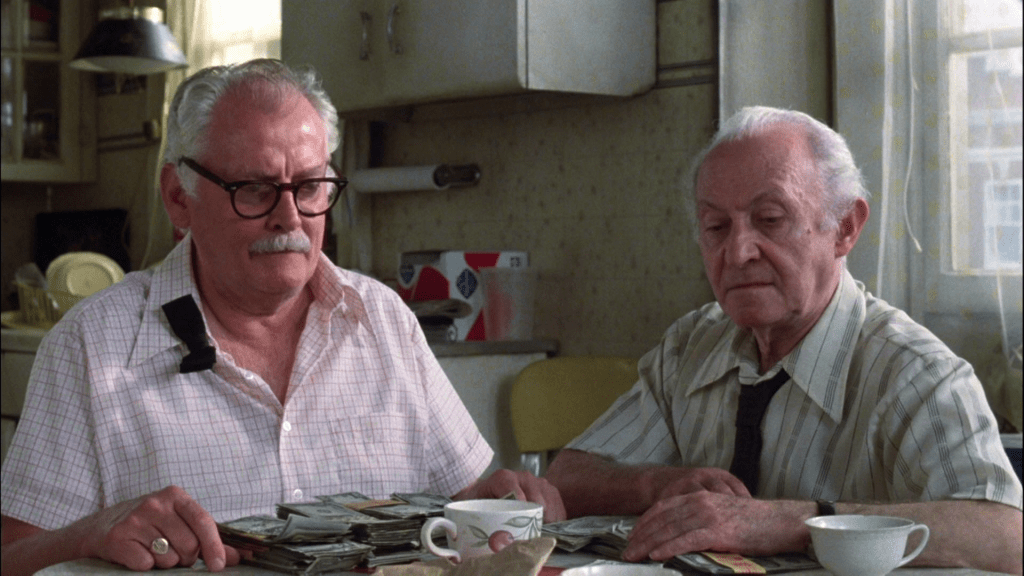

Prior to making one of the biggest action comedies of the 1980s (and one that is now in the process of becoming a Netflix reboot) in the Eddie Murphy starrer Beverly Hills Cop, Martin Brest made this decidedly low key heist film about a trio of elderly pensioners (played by George Burns, Art Carney and Lee Strasberg), who are totally bored with their lives and decide that, with nothing much to lose, what would be the risk in robbing a bank if it gave them some much needed adventure?

The film was actually remade in 2017 by Zach Braff with Morgan Freeman, Michael Caine and Alan Arkin replacing the original cast members. Despite this, the original remains a sorely underseen minor classic, a film that is played for laughs but retains a poignant touch throughout.

A whimsical film, gently paced, and featuring three fantastic performances from its leads as widowers who simply want to feel young again. Perhaps the key to this picture being charming and engaging is that the characters are treated with respect and the humour that arises from their unusual decision occurs naturally, with Brest painting a pertinent picture of what it’s like to be old, retired and forgotten in the ever bustling New York City.

The Anderson Tapes (Sidney Lumet, 1971)

Sidney Lumet is one of the greats of cinema, and the 1970s is arguably his most successful decade as a filmmaker, releasing such classics as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon and Network. However, at the beginning of the decade, he teamed up with Sean Connery to make The Anderson Tapes, about a thief who reenters society after 10 years in prison and immediately plans his next heist.

The building he decides to rob is the upper scale apartment block his girlfriend resides in, and, unbeknownst to him, his moves are being recorded. The film features a stellar cast aside from Connery, including Dyan Cannon, Martin Balsam, Ralph Meeker and a big screen debut for a young Christopher Walken.

Like most crime capers, not everything goes to plan, and an array of unfortunate events lead our protagonist into some sticky situations, but that’s all part of the fun of course. Lumet directs with his typical no nonsense style, allowing the cast of eccentric characters to lead the story, but still imprints some stylish visual flourishes upon the film. A somewhat forgotten success in his hugely successful filmography.

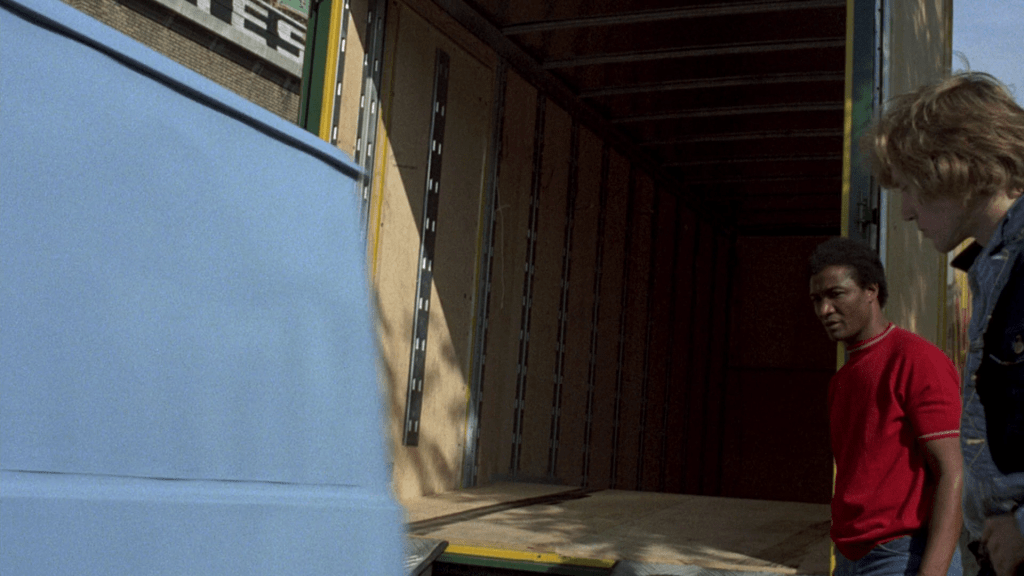

Coffy (Jack Hill, 1973)

Pam Grier is perhaps most well known to modern audiences as the star of Quentin Tarantino’s 1997 film Jackie Brown, but in the 1970s, she made a name for herself as the star of several blaxploitation flicks, and indeed that was the reason Tarantino picked her to be the protagonist of his 3rd feature.

Coffy is one of the best films she made during her prolific period and marks the 2nd collaboration out of 3 with director Jack Hill. She stars as the eponymous “Coffy” Coffin, a nurse who sets out on a bloody trail of revenge after her younger sister is injured by some contaminated heroin.

This is a downright dirty and sleazy picture, featuring drug dealers, pimps, prostitutes, mobsters and all sorts of unsavoury characters. Vigilante vengeance missions were popular in the 1970s and it doesn’t get much more cynical or messy than this.

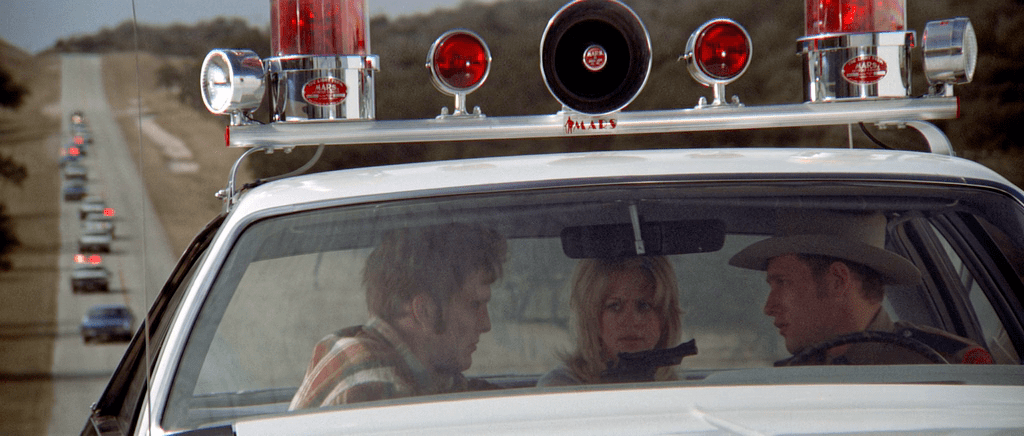

The Sugarland Express (Steven Spielberg, 1974)

A Steven Spielberg film in a list of underrated pictures? This may seem like a contradiction in terms, but actually, prior to 1975’s Jaws, Spielberg was an independent director trying to make a name for himself in the moviemaking business.

The Sugarland Express is one of many films influenced by the iconic Bonnie & Clyde, starring Goldie Hawn and William Atherton as Lou-Jean and Clovis Poplin, two small time crooks who lose their baby and go on a rampaging mission to get him back.

Part road movie, part lovers on the run, part hostage thriller, this is a multi faceted movie that also deals with the sensationalist fame that often happens when the media gets a hold of a particularly saucy criminal situation. The two lovers are forced to drag a captive policeman all over Texas in their mission to get their baby back, and Spielberg displayed that, even before the gargantuan budgets of his later movies, he was a real cinematic talent. Unfortunately now somewhat forgotten considering the scale of his future blockbusters, The Sugarland Express is well worthy of a viewing as it still holds up magnificently.

The Hot Rock (Peter Yates, 1972)

Crime capers have been done so often that it is perhaps one of the hardest genres to stick a degree of originality upon. They tend to have similar plots and story conventions, and while some directors may try a different take on the heist genre, they often end up falling short.

Peter Yates, already an established filmmaker following his Steve McQueen classic Bullitt, would have been well aware what a difficult undertaking it is to make an original heist film, so instead, he went along a safer route. With The Hot Rock, he didn’t try anything particularly new or inventive, but crafted an immaculate, tightly paced heist comedy that is simply a lot of fun and the set pieces get progressively bigger and more daring without him ever losing control.

Robert Redford is an ever reliable lead in a charming film that also features the likes of George Segal, Ron Leibman and Moses Gunn. Witty, entertaining and a strong influence on Steven Soderbergh for his Ocean’s trilogy.

Charley Varrick (Don Siegel, 1973)

Following up the iconic Clint Eastwood starrer Dirty Harry was never going to be an easy task, but Don Siegel did a fine job with the under appreciated Charley Varrick.

Walter Matthau, a man who seems to have been nearing retirement his entire career, stars in the lead role as a guy who robs a small bank in a non descript small town but soon discovers that the money obtained actually belonged to the mob. Now he has to evade both the mafia and the police in dusty rural New Mexico.

Matthau is typically brilliant as the world weary Varrick, employing his usual brash cynicism in his uniquely charming manner. Siegel directs with a lack of sentimentality and things inevitably go wrong as plans are scuppered. Charley Varrick isn’t quite the household name that Clint Eastwood’s franchise detective became, but he deserves a second look in this slow burning heist thriller.

Black Caesar (Larry Cohen, 1973)

“Paid the cost to be a boss”. So goes the chorus in James Browns’ theme song for Larry Cohen’s rise and fall crime story Black Caesar, a tune that features prominently throughout the film to great effect.

Fred Williamson stars as Tommy Gibbs, a guy who witnesses police violence from an early age growing up in the ghetto, and grows up to become a formidable criminal.

Black Caesar is a loud and angry film, taking direct aim at the racism that plagues society with fervent vigour. There are several scenes of shocking violence and the tone remains consistently dark, with the tragic ending foreshadowed from the beginning. Cohen was well known for inserting political undertones into his exploitation pictures but here he goes full throttle, unleashing a flurry of attacks on the corrupt capitalist regime that allows discrimination and inequality to thrive. Williamson is a stunning lead in this red hot, unrelenting tale of a man who stops at nothing to get to the top.

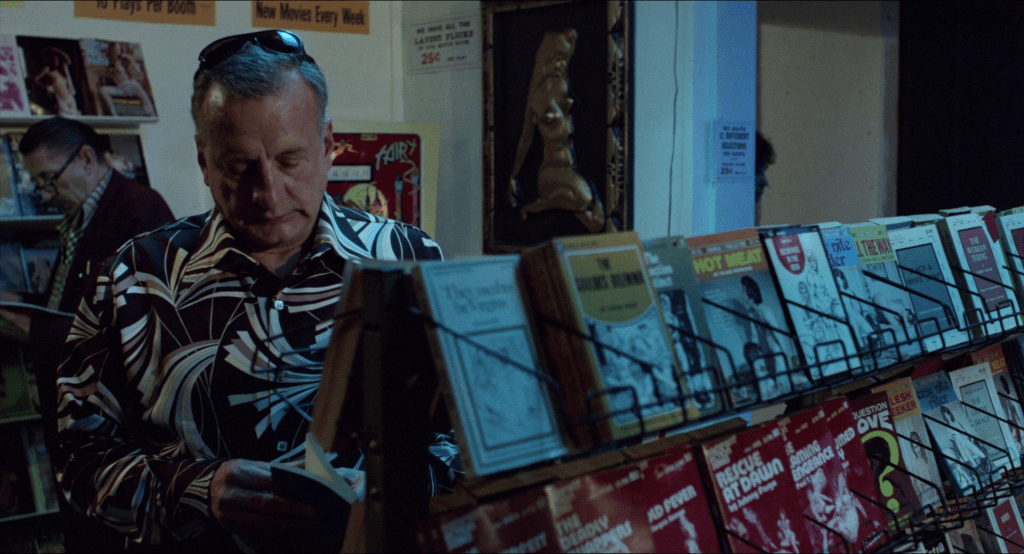

Hardcore (Paul Schrader, 1979)

Paul Schrader is probably best known for his incendiary collaborations with Martin Scorsese, not least of which writing the scripts for Taxi Driver and Raging Bull (Schrader famously kept a loaded gun in his desk when writing Taxi Driver, which should give an indication of the kind of storyteller he is). He is an extremely accomplished director in his own right though.

His debut feature Blue Collar, about a group of fed up workers who rob a safe at their union headquarters in retaliation at their corrupt bosses, would also have been a more than apt pick for this list.

His second feature Hardcore, is the film we will be showcasing today though. The film stars the late grizzled great George C. Scott as Jake Vandorn, a conservative midwest businessman who is deeply religious and about as far removed from the world of pornography as one can imagine.

However, when his daughter goes missing, he is forced to embark on a trip to the Californian sex scene in order to try and rescue her. As he goes deeper and deeper into the sordid world of pimps, prostitutes and pornographers, he has to reckon with the realisation that she might not want to be found.

Schrader’s religious upbringing informs the film’s subject matter, and despite the initially disagreeable nature of Vandorn, the film is much about his personal journey of discovery as it is about his quest to find his daughter. The story becomes bleaker and darker as it goes on but it is not without some hope, and this modicum of optimism manages to restrain the otherwise utterly sombre atmosphere. A voyeuristic dive into a bleak world with a towering lead performance and several sections of cinematic revelry that have to be seen to be believed.

Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 1975)

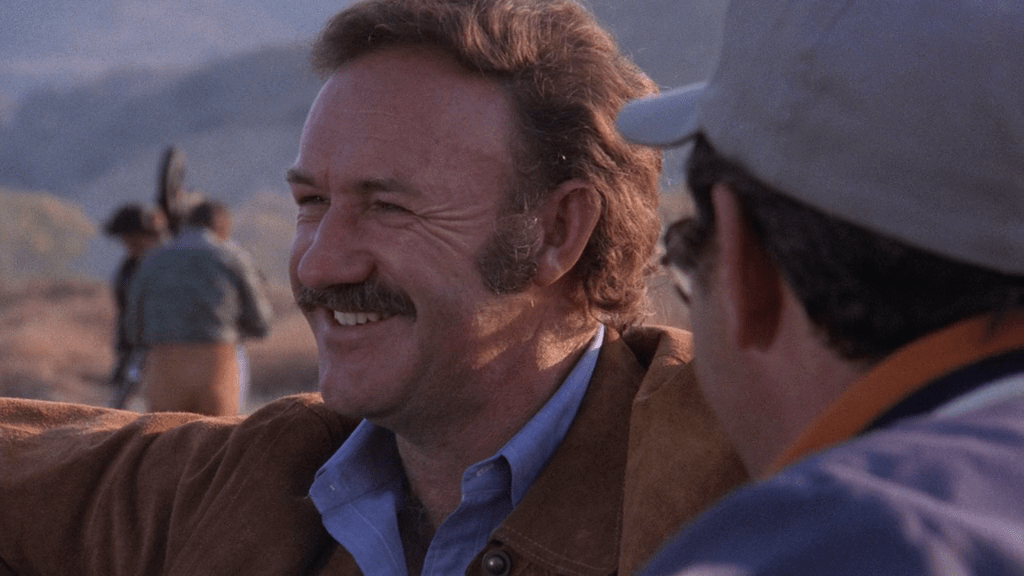

Last but certainly not least is Night Moves from director Arthur Penn of Bonnie & Clyde fame. This 1975 neo-noir stars Gene Hackman as Harry Mosby, a private investigator, who, in typical cinematic fashion, has an utter mess of a home life and uses his job to try and deflect from the fact he is completely miserable.

Mosby is a former football player who was once well known but is now middle aged, balding and going nowhere in particular. His girlfriend is cheating on him and his PI business isn’t particularly financially successful. So when he takes on a case involving the missing daughter of an ex Hollywood actress turned bitter alcoholic, he finds himself engrossed and there are several twists and turns as the case becomes more and more dark and dangerous.

Hackman embodies the role of the dishevelled Mosby and the film is certainly ambitious as it sees him travel from California to Florida and back again several times in his quest to unravel the details of what’s going on, and inevitably the more he investigates the more complicated it becomes.

Night Moves is one of those films that doesn’t hold its viewers’ hand, and may even leave a bit of a sour taste as the credits roll as there are no satisfying conclusions. This is the point Penn was trying to make, however, and his unrelentingly cynical film is full of biting satirical dialogue, egotistical characters and stunning locations. A mind bending, cynical classic and one that deserves more attention today.