I’ve fallen in love with her. Her accent is foreign, but it sounds sweet to me. We were born thousands of miles apart, but we were made for each other.

— Peter (David Niven)

War films are one of the long-standing staples of the movie industry and perhaps no single war has seen more depictions than World War 2. In 1946, just one year after the Nazis were defeated, Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger used it as the setting for one of their grand productions. But this is no ordinary war movie. WW2 is merely a backdrop for an endlessly inventive, rousingly romantic and endearingly whimsical tale of a British man and an American woman falling in love against all odds.

The basic premise centres upon a a British aviator (played by David Niven) who is supposed to die when he leaps out of his burning bomber plane without a parachute. Miraculously he survives, and it is determined by an afterlife court that he has somehow cheated death, thereby breaking universal law, and this must be rectified by recalling him to heaven. The problem is that he doesn’t want to go as he has fallen in love with the American radio operator (Kim Hunter) who picked up his call before he fell. The nature of mortality and love are brought into question as he must stand trial in an outer world court to prove his love is genuine and determine whether he will live or die.

It’s a love story like no other and indeed a film with no real equivalents. Elements of other films do come to mind. Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life employs similar motifs, where a suicidal James Stewart is shown by an angel what life would be like in his small town if he were never to exist. However, A Matter of Life and Death takes on an altogether more grandiose approach to its themes and utilises stunning visual effect techniques to portray its subject matter.

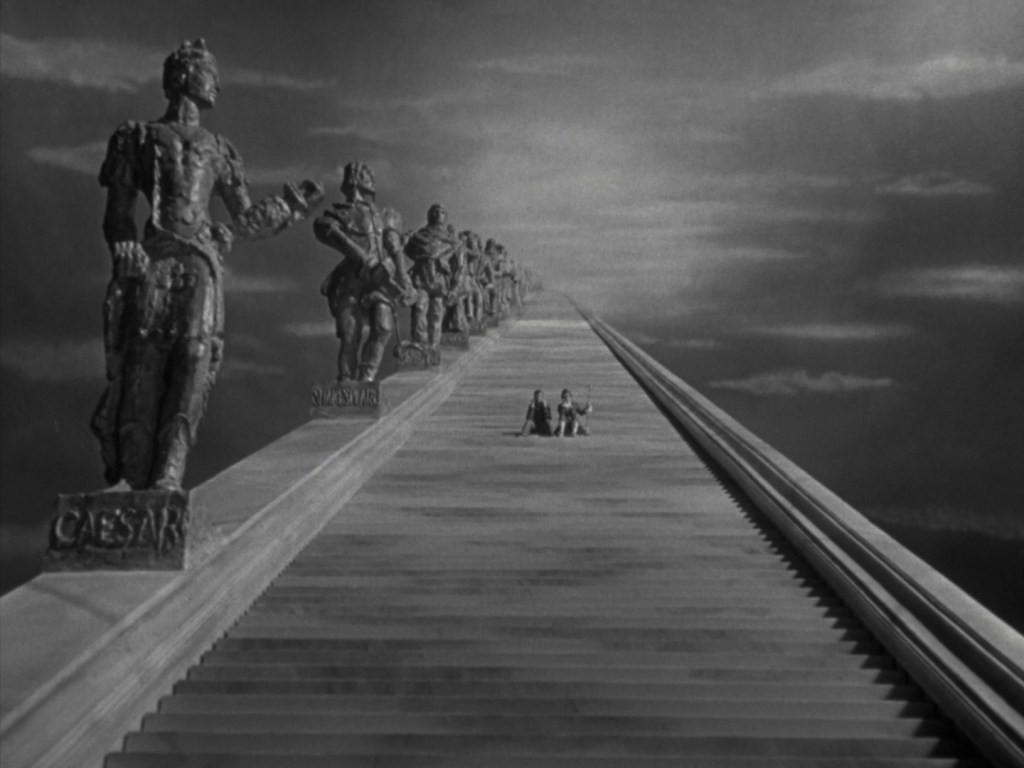

Made in a time well before CGI was even invented, let alone standard practice in the movie industry, Powell & Pressburger had no choice but to be creative with their visuals. The lack of technology at their disposal led to creativity that knew no bounds. From the stirring opening exchanges, as Niven falls in love with Hunter while escaping a bomber plane on fire, to the fantastical production design of heaven itself, the visuals are breathtaking. Thousands of extras make up the crowd in the trial scene, in an amphitheatre reminiscent of the Roman coliseum. Although heaven does look gloriously otherworldly, the practical effects and real life people make it that much more believable and admirable.

A small yet ingenious subversion of expectations was to shoot the Earth scenes in glorious technicolour, whilst the Heaven scenes are in black & white. When cutting from one place to another, colour fades into the screen and vice versa. It’s a striking way of showing us the true beauty lays in being alive and that our two protagonists are youthful and full of exuberance with long, grand futures ahead of them. There are many neat visual tricks and flourishes like this including a grotesque yet wondrous shot of an eyelid closing during surgery and some handheld camerawork of a motorcycle crash that has to be seen to be believed.

If the film falters at any moment, it is perhaps during the trial scene, which becomes a little too entrenched in its British versus American debate and occasionally strays away from the romance which makes the story so appealing. There are grounds for this, however, and at the time the film was made that was very much a topical debate. The trial is built up to with strong narrative pacing and leads to a sentimental yet well earnt finale. The content of the film is so doggedly romantic that ending with the message that love conquers all does not feel remotely out of the realms of reality within the context of the film’s universe.

Suspension of disbelief is welcomed for this epic tale, but it does not feel like lazy writing to have the two leads fall in love in a matter of mere minutes. Their encounter is explosive and dynamic and sets the tone for the rest of the film which never lets up in terms of being earnestly and unabashedly romantic but also not so self-important as to be unable to poke fun at itself. A small meta moment occurs when an angel enters the real world from heaven and declares how refreshing it is to see in technicolour for once. It is this valiant combination of rousing romanticism with an adeptly light touch of whimsy that makes the film so engaging.

Powell & Pressburger were so ahead of their time with their visionary masterpieces that their works still astound and shock to this day. And they were a perfect match for each other. According to cinematographer Jack Cardiff (remarkably this was the first feature that Cardiff shot), Powell was the risk taker of the two. He was full of wild ideas and would push and push until sometimes he got a little ahead of himself but Pressburger was always there to reign him in and maintain structure and focus. As such, they enjoyed many successful collaborations together and perhaps it is not a surprise that neither’s careers were particularly fruitful after they parted ways as filmmaking partners. Their time together could not be replicated but thankfully they were prolific, and A Matter of Life and Death stands impressively tall amongst their many towering pieces of art.