I don’t want to give you a gun to kill me. I’m giving you a spade, a spade.

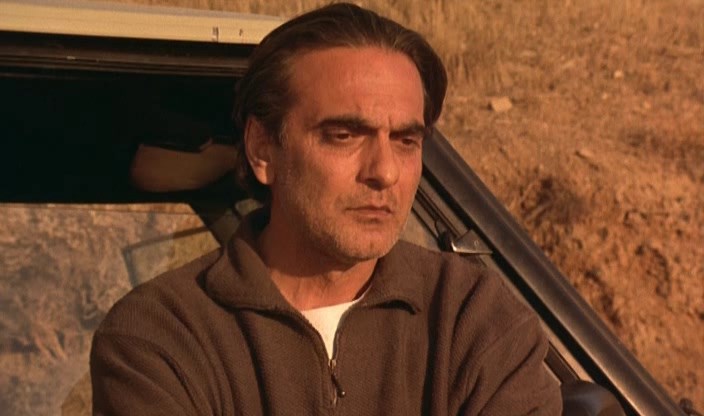

-Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi)

A man drives around Tehran and its outskirts, searching for passengers to pick up and offer a job. At first his journey seems aimless, but soon it becomes abundantly clear. The man, named Mr Badii (Homayoun Ershadi, in a remarkably assured performance that belies his then non-professional actor status) wants to kill himself and he needs someone to bury him once he is dead.

His identity is ambiguous. There is little background on him. We do not even learn his first name. In a conversation with his first passenger, a young Kurdish army man keen to get to his barracks on time, he reveals that he too used to be in the army. However, and this is vital, we do not ever learn why exactly he wants to kill himself. Why now? At what point did he decide ‘enough is enough’ (as he so succinctly puts it)? These questions and more are posed in this poetic masterpiece from acclaimed Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami.

The reasoning behind his decision for suicide never being disclosed is a narrative choice which is directly opposed to the sensibilities of Hollywood and western filmmaking in general. As such, some may find it somewhat jarring and difficult to connect with as it is not a straight forward narrative. They would not be alone should they be put off by the film. The late great critic Roger Ebert famously named Taste of Cherry as one of his most hated films and declared it to be ‘excruciatingly boring’, proving that even the most esteemed of critics can get it wrong sometimes.

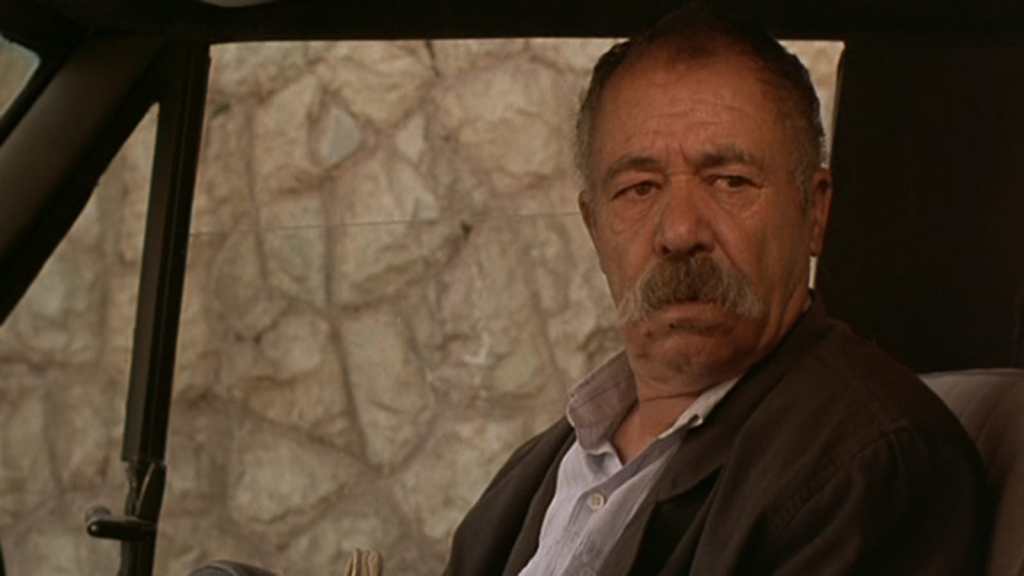

For this writer however, the lack of emotional backstory to the protagonist renders the story more universal and soon the viewer becomes attached to him by mere virtue of being a voyeur on the ride with him throughout. He picks up several different passengers along the way, each offering different reasons as to why he should not kill himself. He remains stubbornly adamant and even grows frustrated that nobody will help him. He receives advice from a perturbed young soldier, an Afghani security guard, a religious student and finally a wise old Turkish man who imparts some of the most philosophical and affecting advice.

A bleak desert landscape on the outskirts of bustling Tehran is a central character here too. Wide shots show Mr Badii’s car twisting and turning over the dusty terrain as he engages in debate with his various passengers. The car is often shown from afar, but the dialogue is always heard as if up close, maintaining a constantly intimate relationship between viewer and protagonist. Although we may not know much about his background, nor do we ever learn much, we grow close to him because he is always with us. Of course, a major part of the pathos is down to the stunning performance by Homayoun Ershadi. As I mentioned above, he was a non-professional actor at the time and was actually discovered by Kiarostami for this particular film. It seems to beg belief that he’d never acted in a film prior to this, for his performance is utterly assured and mature. His face emanates grave wisdom and he utters philosophical, dark lines with an intellectual quality and a quiet intensity.

When there are close ups, they focus on either Badii’s face or the face of his passenger. It is rare for the two to be in a shot together and this is because Kiarostami was behind the camera in the seat next to his actors and speaking the dialogue to them himself, encouraging them to come up with their own answers to his questions. This method allowed for lots of improvised dialogue, which is especially impressive because much of it feels well rehearsed and scripted.

There is no score for almost the entirety of the film, but the sounds of the desert form a kind of melodic backdrop for the scenes. Tyres running steadily over gravel, the car engine rumbling, the wind blowing, leaves on trees swaying, even police sirens whirring in the background to give one a reminder this harsh landscape is just outside a city.

The meditative approach of the majority of the film comes to an extraordinary and ultimately ambiguous conclusion as thunder rumbles in the dark morning hours before the sun has risen and we are faced with the blinking eye of a storm before being plunged into total darkness. What follows, I will not spoil, but it leads the viewer to question the reality of everything that has preceded and ruminate on the artificiality of filmmaking in general.

The film moves at a slow pace, true, but this allows it to breathe and the runtime of 95 minutes is far from off-putting. The tension builds ever so subtly with a delicate, touching and sometimes even humorous tone that when the inevitable climax takes over it is impossible to tell what Mr. Badii is going to do. The power of Taste of Cherry lasts for a long time after the end credits have finished rolling and certainly encouraged this writer to finally get to grips with more works from Kiarostami and more Iranian cinema in general.